Risky Finance has crunched the year-end regulatory filings for the biggest 11 global banks. For those who aren’t subscribers to the full database, here are some of the key trends we noticed.

Troubled Deutsche Bank is on a mission to cut its complex balance sheet and reduce risk, and at first sight, the numbers bear that out. The bank shrank its derivative assets by more than 15 per cent in 2018, and its total assets by more than 12 per cent.

However, Deutsche’s regulatory capital requirement or risk-weighted assets barely went down despite credit and operational RWA reductions of five per cent apiece. The culprit? An unexpected 15 per cent increase in market RWAs that was caused by the balance sheet reduction.

It sounds like a contradiction but a paragraph buried in the bank’s annual report explains why.

“The increase was primarily driven by stressed value-at-risk”, Deutsche said, “coming from a reduction in diversification benefit due to changes in the composition of interest rate and equity related exposures”.

So according to Deutsche’s calculations, that bloated, complex derivatives portfolio would actually be helpful in a 2008-style crisis when correlations all went to one, because the exposures offset one another. The idea is not totally far-fetched: remember how Gregg Lippmann’s famous ‘big short’ helped save Deutsche in 2008?

It’s a bit like saying that nuclear power stations don’t melt down when all the components are aligned properly. But what happens when things go wrong? As Deutsche Bank is telling us, when the portfolio is being dismantled, it becomes even more dangerous.

It was the big story at the beginning of last year, how a South African retailer came unstuck with accounting irregularities, ensnaring the global banks like Bank of America and HSBC that extended margin loans to its largest shareholder. It was that rare thing these days: sudden hefty impairments on investment grade corporate loans.

When we published a story about it in March, we noticed how JP Morgan and Citigroup did things a bit differently, booking the loans through their securities financing business, incurring mark to market losses when the value of the equity collateral plunged in value.

A few months later, JP Morgan did something quite dramatic: it reduced its securities financing exposure by $130 billion. This wasn’t reported by any news organisation, perhaps because the disclosure to the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council never appeared in an SEC filing.

In this disclosure, there are two types of securities financing exposure reported, and the second one in which margin loan collateral is reflected in JP Morgan’s loss-given default (LGD) model saw the $130 billion decrease. The other type of exposure stayed constant, but saw an equally dramatic rise in its capital requirement.

One might detect the hand of the New York Fed here. Until Steinhoff, JP Morgan appears to have run its collateralised margin lending on the tiniest sliver of capital. Without that advantage, the bank saw no point in operating in this market, and made a quiet exit.

Of course it never completely went away – the 11 banks in the Risky Finance database have $800 billion of securitisation exposure between them. But after years of slow decline after the financial crisis, 2018 was the year that securitisation bounced back.

$48 billion of new exposures appeared on the balance sheets of BNP Paribas, Barclays, Citigroup and Deutsche Bank, offset by about $20 billion of reductions at the likes of Goldman, HSBC and Wells Fargo, where legacy portfolios continue to run off.

When you look at the contribution of new securitisation to credit RWAs at the banks, you can see why they are doing it – the impact on capital requirements is tiny. And that’s the whole reason for securitisation in the first place: the tranching of exposures in a waterfall of losses which gives huge risk transfer benefits to originating or sponsoring banks.

The financial crisis cast a long shadow over this market. The most toxic parts of it, like correlation trading or asset-backed CDOs, have all but disappeared. But collateralised loan obligations are in rude health, with BNP Paribas having done $20 billion of them last year, while Barclays structured $6.7 billion of synthetic CLOs. Mortgage-backed securities origination also saw a comeback, with Barclays doing $11.5 billion of European MBS, while Citi ramped up its private label MBS and asset-backed financing to the tune of $16 billion.

These are modest numbers compared with pre-2008 but are significant nonetheless.

Levelling the Playing Field

Levelling the Playing Field

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

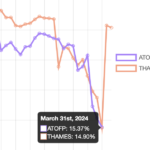

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital