I wrote this article before the 2015 UK General Election but Channel 4 asked me to keep it under wraps so not to give away what I was working on. Now that my documentary on LOBO borrowing has been broadcast, the article provides a broader perspective. The premise is that at the local government level, there exists data that allows us to test the link between political complexion and financial competence in a simple way.

The UK government compiles data on £63 billion of loans it has made to some 485 UK local authorities via the Public Works Loan Board and publishes it on the Debt Management Office website. The councils are free to choose the maturity of their loans, which because rates are volatile, amounts to a risk management decision. If rates rise, variable rate or short term loans will prove expensive. If rates fall, longer-term fixed rate loans become a burden. With a sustained fall in sterling rates since 2009, it is the latter that happened.

In the above visualisation I have tried to show how councils addressed this problem in several dimensions. The horizontal axis shows the weighted average remaining maturity of each authority’s loan portfolio. The vertical axis shows the weighted average interest rate they are paying the government on this portfolio. The circle representing each authority is sized according to its outstanding loan balance and coloured according to political control. I performed this exercise for the years 2015 and 2012. If you click the selector at the top right, you can see the changes that occurred over a three year period that included a major set of local council elections (warning: watching the dots move and change colour is addictive).

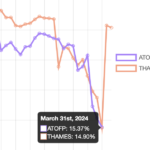

If there is any general election nugget from this data, it is the fact that blue dots tend to be clustered towards the bottom while red ones float to the top. In other words, Labour councils pay on average more interest to the government than Conservative ones. In 2012 this difference was 78 basis points per year; by March 2015 it was down to 48bps. For an average-sized loan of £100 million, that works out almost £500,000 per year. So-called hung councils – those with no overall political control (NOC in the chart), pay even more than Labour, with a 62bps interest premium over Tory-run authorities.

Does this correlation imply causation? Conservatives might leap at the chance to claim superior financial management skills at local government level – vote Tory in order to pay lower interest on loans. Before we make that leap, lets look at the data more carefully. Leave aside the fact that the averages hide a lot of variance. Yes, there are Tory councils (like Kent) paying high interest rates, and Labour ones (such as Reading) paying low interest. The trend is clear enough.

Could there be some factor correlated with Labour support that also leads councils to borrow more expensively? We know that Labour councils owe the central government almost twice the amount (£25 billion) of their Tory counterparts (£13 billion). But in itself, that shouldn’t be a surprise. Urban status correlates with Labour voting, and cities have higher population densities that require higher capital expenditure, hence borrowing. The fact that they have to borrow more shouldn’t mean that they have to pay a higher interest rate for the privilege.

As I mentioned above, the key risk management decision in borrowing is the period over which the interest rate is fixed. At first sight there is no distinction between councils of opposing political stripe: Tories and Labour alike have portfolios that mature in about 22 years on average. However, the maturity dates don’t tell you when the loans were first taken out. If Labour or hung councils borrowed earlier, when rates were higher, that might explain the difference.

This leads us to the question why these councils locked themselves into paying higher rates for such long periods. If had councils borrowed for shorter periods, they would have benefited from the plunge in short-term borrowing costs after the financial crisis, potentially saving hundreds of millions of pounds a year. The UK government, which has about a third of its fixed rate liabilities with a maturity below five years, has benefited in this way1)the UK government also has large index-linked liabilities, but these have become cheaper to service as inflation has fallen.. You can argue that since we are looking at councils borrowing from the central government, which in turn covers about two thirds of council expenditures with direct grants, it doesn’t really impact taxpayers overall. However, at local level, in a time of budget cuts, such savings make a difference.

The fact that the hung councils or ‘NOCs’ did worst suggests that the ultimate reason for the differences in borrowing rates is to do with governance. Elected councillors don’t make day to day borrowing decisions; they delegate this power to staff in council finance departments. What they can and should do is scrutinise these decisions and push back against the group-think that seems to afflict council finance professionals and their advisers. Are councillors at NOC authorities too busy bickering to do this? Are Tory councillors, who are more likely to have a financial background, better at challenging officials on borrowing decisions than their Labour counterparts?

I don’t know the answers to these questions, but that data suggest that all local politicians and those who elect them should look more carefully at how their local councils do their borrowing.

References

| 1. | ↑ | the UK government also has large index-linked liabilities, but these have become cheaper to service as inflation has fallen. |

Levelling the Playing Field

Levelling the Playing Field

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital