The executive order by President Donald Trump last week to review the Dodd-Frank Act – which he called ‘a disaster’ – may not end up overturning the 2012 law signed by his predecessor. But the move signals a rollback of the great regulatory march that started with the 2008 financial crisis.

Even before Trump’s election victory, there were signs that a high water mark had been reached, such as the strong opposition to Basel IV from European banks. Back then, the US was leading the march towards tougher rules.

Trump’s words have to be taken together with the letter from US House financial services committee vice-chairman Patrick McHenry to Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen, calling on the Fed to desist from any international bank regulatory discussions.

As Trump is already discovering, constitutional checks and balances can stymie his plan. The Fed has considerable independence, although less than the judiciary. But if Trump and his congressional backers get their way on financial reform, America will become an anti-regulatory champion, and that could have profound international consequences.

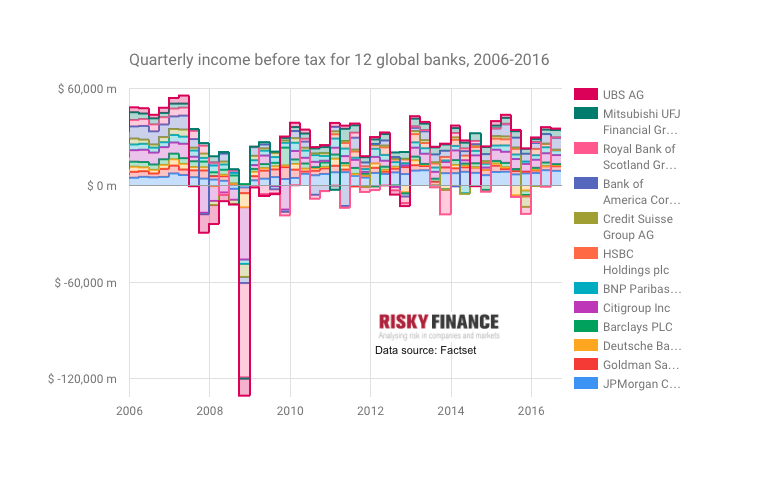

To help think about what all this means, Risky Finance prepared two charts. The first shows quarterly pre-tax income for twelve global banks from 2006 to 2016 (provided by Factset). Anyone who forgets why Dodd-Frank and other regulatory reforms came into existence should look at this chart.

In the fourth quarter of 2008, these banks lost a total of $130 billion, prompting government bailouts and trillions of dollars in support for their leveraged balance sheets. At first glance, things recovered quickly. It took only 18 months for the banks to earn back the money lost in 2008, although the long-term average quarterly profit has never returned to pre-crisis levels.

However, the chart understates the problem, for two reasons. First, it only includes banks that survived the crisis, and leaves out those that either went bust or lost money for shareholders before being taken over. And even for the 12 surviving banks, the impact of rights issues and bailouts mean that shareholders from the pre-crisis era suffered heavy dilution.

Then there is the wider impact to consider – on investors who bought structured securities linked to mortgages, and US homeowners whose homes were foreclosed, or those who lost jobs in the ensuing recession.

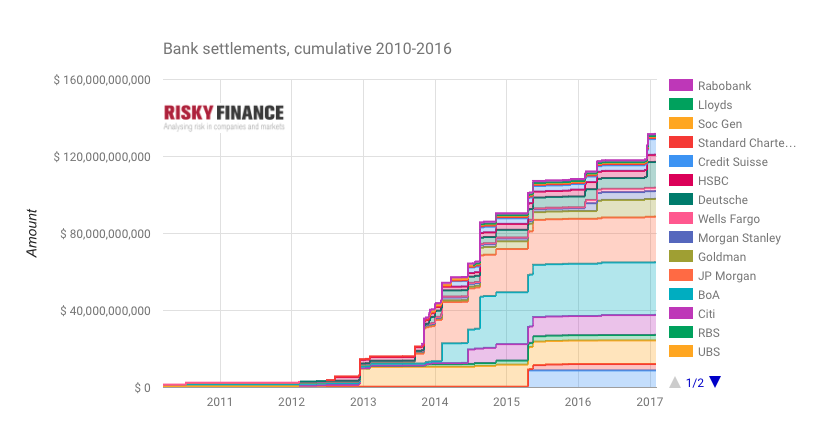

The second chart shows the cumulative amount paid by the shareholders of these banks in legal settlements since 2010, compiled by Risky Finance. As of January 2017, this amount is greater than the losses the banks suffered in 2008. The settlements are related to international activity by the banks, divided into four categories.

The biggest one is the $83 billion of mortgage settlements imposed by US regulators, which punished banks directly for actions that stoked the crisis. In distant second place comes the $19 billion of settlements linked to anti money laundering (AML) rules, sanctions and tax evasion. Close behind that are $17 billion of settlements for rigging interest rate benchmarks such as Libor, followed by foreign exchange rigging settlements.

The most striking thing is that 94 per cent of the $132 billion in total settlements to date has been imposed by US federal regulators, of which 47 per cent are on non-US banks (I am leaving out state-level regulators such as New York’s Department of Financial Services in this calculation). In other words, not only has the US been the key driver behind post-crisis regulatory reform, but it has also been acting as global policeman holding banks to account.

The Trump administration may be focusing on repealing Dodd-Frank as a domestic matter. It may be possible to secure eight years in the presidency by stoking a credit bubble that puts cash in the pockets of the stagnant middle class. All it requires is a certain amount of forgetting.

But if this comes with a US retreat from a global regulatory role, then the consequences would be profound – not least because US firms dominate global investment banking. Would any other national regulator step into America’s shoes? Would they dare to exclude US banks from their markets? I doubt it. In the world of finance, the change would be as significant as the US withdrawing from NATO.

Levelling the Playing Field

Levelling the Playing Field

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital