In 2017, nothing succeeded like size in the US stock market. For the S&P 500 that resulted in a 2017 return of 19 per cent versus the small-cap Russell 2000 which delivered only 13 per cent.

But even within the S&P500 index, size was a winning bet. A portfolio of the five largest companies weighted by market cap – Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook – would have netted a return of 43%, more than double the return on the index itself.

Start with an overview of the S&P500 component companies, shown in the chart below where the squares are sized by market cap and coloured according to year-to-date return.

When we last reviewed the sizes of S&P stocks two years ago, the dominance of the largest companies was already striking. Just 50 of the biggest stocks accounted for more than 50 per cent of the index market cap. Has the effect become more pronounced today?

Back then, we quantified the size distribution of S&P stocks using the so-called Lorenz curve (see chart below). The ratio of the areas below the curve and straight line is known as the Gini coefficient, which is used to measure income or growth inequality 1)this approach was first applied to equity portfolios by the quant Thierry Roncalli in a paper published in 2011 so this chart should arguably be called a ‘Roncalli curve’.. However, the Gini coefficient of the S&P 500 has only increased by three percentage points since 2015, to 62%. But the Gini coefficient has been criticised by economists studying inequality as being insufficiently focused on the extremes.

To really appreciate what happened in 2017, we need to compare the increases in value of the companies. The best way to think about that is construct a hypothetical portfolio ranked by market cap at the start of the year, and see what the effect on year-end value is when stocks are successively added starting with the biggest.

In 2016, the 250 biggest companies at the start of the year accounted for some three quarters of increased value at year-end. But in 2017, the 250 biggest S&P 500 members delivered 90 per cent of increased value. Or putting it another way, the biggest 50 companies in the index provided more than half of the value increase.

The charts below show the effect. The left chart shows the increase in market cap, while the right chart shows the cumulative weighted return as stocks are added. Each bar in the chart represents a single S&P stock. The width of each bar is proportional to the start-of-year market cap, and the height is the cumulative weighted return of the portfolio containing the biggest stocks including that company (mouse over the charts to see the individual companies).

|

The remarkable thing about this performance is that diversification doesn’t seem to help. After the top five stocks listed above, adding more to the market-cap weighted portfolio only lowers returns, eventually converging on the index return once all 500 stocks have been added. In 2016 it required 18 stocks to reach the highest return.

As I wrote two years ago, such a result suggests that tracking the entire index is a wasted effort (at least when dividends are ignored). A handful of the biggest stocks are all one needs.

There are other questions that spring to mind. Is it healthy for US equity wealth creation to rest on the shoulders of five exceedingly powerful tech companies with quasi-monopoly characteristics? Here the debate mirrors the existing discussion over wealth inequality.

There’s also a question about risk. The realised volatility of the S&P 500 reached record lows in 2017, while the volatility of the five largest component stocks was about four or five times larger. If you adjust returns for risk (dividing by volatility for example), then the index looks like a better bet.

But that implies that the higher volatility of a stock like Apple is ‘bad’, when in 2017 most of it was the shares leaping upwards in price (volatility treats upward and downward moves equally).

To understand what is happening, we need another measure – dispersion – which we define as the standard deviation of the returns of all the S&P 500 constituents. In 2017, index dispersion was 54 per cent, more than double its 2016 figure of 24 per cent.

Mega-cap companies with extreme returns tended to be on the positive side of the distribution, with the single glaring exception of General Electric. In other words, picking the largest members of the index was enough to capture this extreme upside, and filter out the extreme downside.

As a result, investors seem to believe that the real risk today is not volatility, but missing out on 40 per cent plus returns. That defined the winner-take-all market of 2017. The question for 2018 is whether that bet will carry through for another year.

References

| 1. | ↑ | this approach was first applied to equity portfolios by the quant Thierry Roncalli in a paper published in 2011 so this chart should arguably be called a ‘Roncalli curve’. |

Levelling the Playing Field

Levelling the Playing Field

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

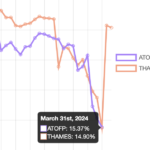

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital