The pandemic has been such a shock to us that an instinctive reaction is to tell ourselves how unique our experience is. Who else understands the special grief of losing someone who in normal times would still be alive? And how special one feels to have learned the personal survival skills and health protocols needed to emerge from the pandemic’s shadow?

But of course our experience is not at all unique. Our ancestors suffered and survived multiple pandemics throughout history. Indeed, in Darwinian terms, our existence today is a direct result of their survival. In the age of Zoom calls, Amazon deliveries and mass vaccination it can be hard to see the relevance of those past lives, precious and unique as they were to those who lived them.

However, Covid-19 levelled the playing field somewhat. In 2020, the helplessness that many felt was not that different to the feeling their forebears had in plague-ridden Restoration London or cholera-afflicted 19th century Europe. And so their insights and memories have something to tell us.

We can find them in great works such as Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year or Albert Camus’s The Plague (long thought of as an allegory of fascism but in fact a book about a plague). I am fortunate to have a direct link to such experiences via family archives.

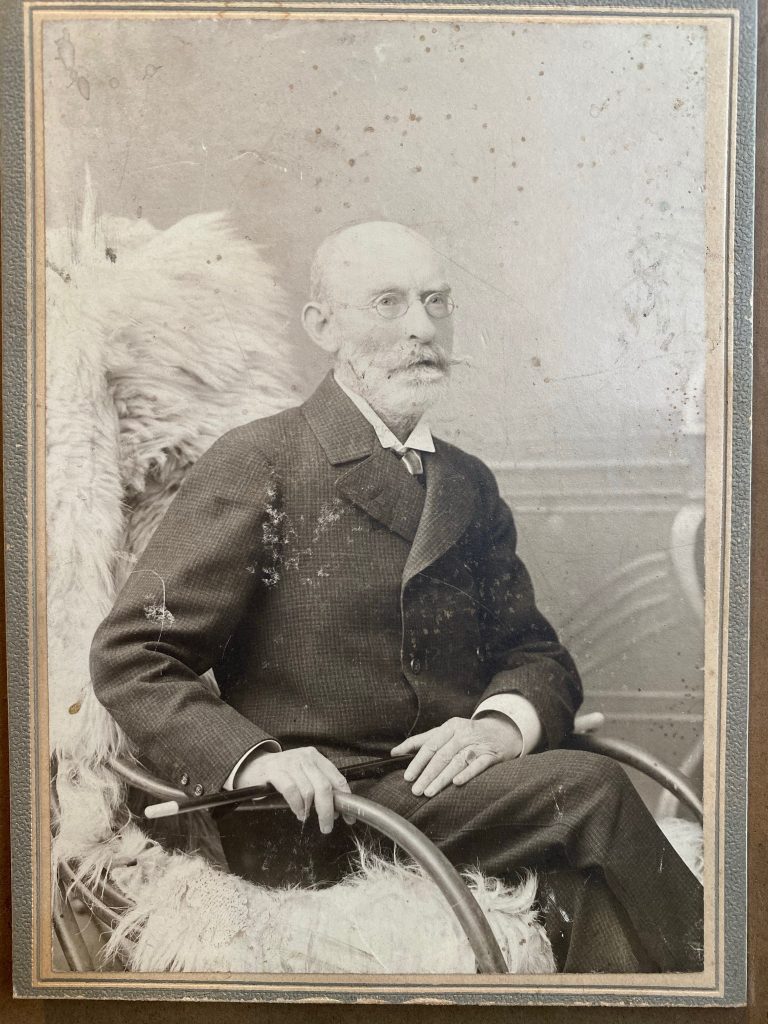

My grandmother Eva Sacher-Masoch died in 1991, but some 20 years before her death she made detailed notes of her mother’s and grandmother’s accounts of growing up in a corner of the 19th century Austro-Hungarian empire. My great-great-grandfather, Dr Wilhelm Ziprisz, played a small but important part in battling waves of pandemics that crossed what is now south-western Rumania.

Ziprisz was born in 1844 in what my grandmother called the ‘old frontier’ of the empire, the land known as Banat, a province recovered from the Ottoman empire at the end of the 18th century. He was from a family of Sephardic Jews originating from Thessaloniki in Greece, who paid for him to attend medical school in Vienna.

While incredibly primitive by modern standards, medicine was becoming a science, helped by visionaries like my great-great-grandfather’s teacher, Professor Ignaz Semmelweis. This Hungarian physician applied empirical observation to obstetric medicine, noting down the survival statistics for mothers whose obstetricians disinfected their hands versus those who didn’t.

Semmelweis’s findings on medical hygiene earned him the name ‘the saviour of women’ on account of the countless deaths in childbirth he helped prevent. He had a great influence on Ziprisz, who turned down the offer of a post in Vienna in favour of starting his own practice in his Banat homeland, where he felt the need for doctors was greater.

After starting his own practice in a town by the Danube river, by around 1870 Ziprisz had found a wife – my great-great-grandmother Theresa Deutsch. According to my grandmother’s account she was just 15 years old when he met her picking flowers, and 16 when they married, against the wishes of her Sephardim parents.

Moving with him to the Transylvanian town of Karansebes, Theresa became administrator of Ziprisz’s medical practice there, while bearing him three sons before she was 20 years old. While Ziprisz was a non-observant Jew, Theresa attended Temple a few times a year. Under the Dual Monarchy arrangement which gave Hungary control of Transylvania, Wilhelm became ‘Vilmos’ and Theresa ‘Terezia’.

Soon after, a diphtheria epidemic struck. This bacterial disease is rare today as a result of vaccination and antibiotics, but back then it was terrifying because of the way it slowly asphyxiated children by creating a swollen membrane in their throats. It was not uncommon for villages to lose all their children in this way.

With his Viennese education, Ziprisz was a pioneer of tracheotomy, or cutting an opening in the windpipe. Combined with his strict adherence to hygiene, it enabled him to save the lives of dozens of children in his corner of Transylvania. According to my grandmother’s account, “Grandfather and Theresa worked tirelessly through days and nights covering long distances”.

To protect his young family, the doctor placed his three sons in strict quarantine with their nanny, but it was not enough. Seeing his three sons stricken with the disease, Ziprisz knew what had to be done but felt unable to operate on them himself. The job fell to a local army doctor who was unaware of Semmelweis’s teachings on hygiene. As a result, the three boys contracted blood poisoning and died.

After the epidemic subsided, Wilhelm and Theresa went on to have three more children, including my great-grandmother. While diphtheria is easily treatable today, this tragic story reminds us just how lucky we are that Covid leaves children almost unscathed.

For Ziprisz and his young wife, it was not long until their next challenge. This time it was one of the great cholera pandemics that swept the world between 1865 and 1883. One of these in 1871 killed 190,000 people in Hungary alone – more than three per cent of its population.

According to the World Health Organisation, untreated cholera has a mortality rate of 25-50% and spreads rapidly when its victims’ uncontrollable diarrhoea contaminates water supplies. Like Covid today, it is a disease of inequality, deadliest for those living in crowded, unsanitary conditions.

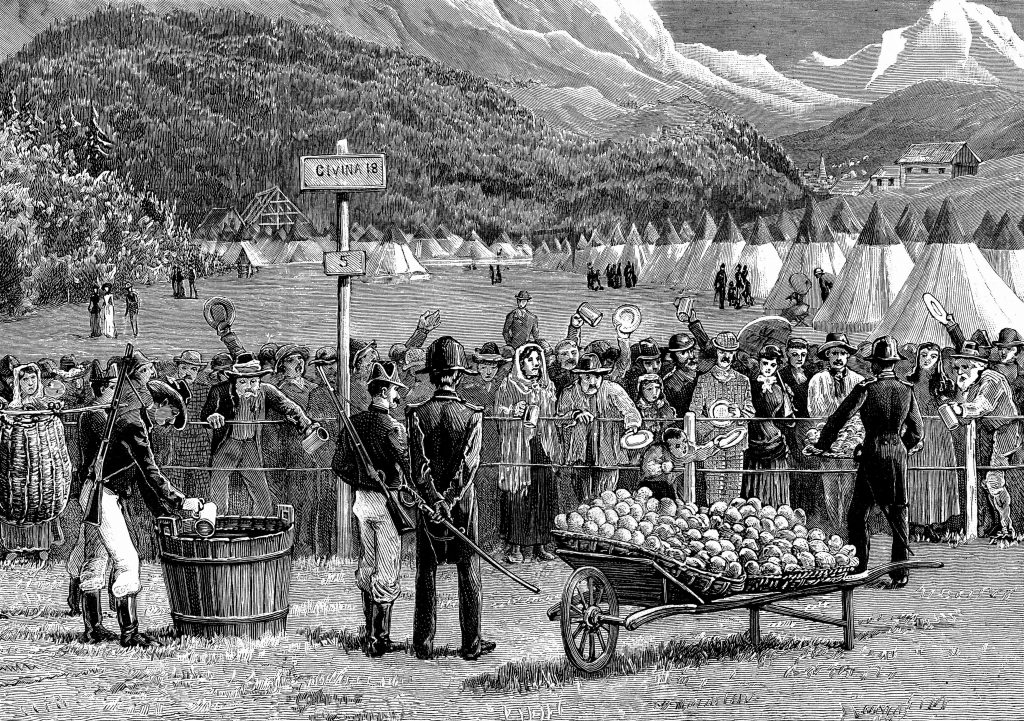

As is well documented, the cholera pandemics would reach Europe via trading routes from Asia and the Middle East, so the Austrian authorities knew what to expect. By the time the outbreak was raging in Serbia, on the south side of the Danube, a complete lockdown was ordered on the northern side. The kind of discipline that some nations now deploy to keep Covid at bay was familiar to our ancestors too.

As my grandmother wrote, “The discipline of the border people in a time of crisis came into play. No civilians were allowed to travel; trading virtually stopped. The guards on the river border were strengthened, and river traffic ceased”.

However, unlike today’s quarantine hotels, travellers stranded in Serbia were forced to stay in a large, squalid cholera camp on the south bank of the river. Predictably, death rates skyrocketed, exacerbated by the lack of doctors in the camp.

Ziprisz volunteered to help, and set off for the frontier 50 miles away with his Serbian servant and a cart loaded with drugs and blankets. My grandmother doesn’t say what these drugs were.

My grandmother later recounted Theresa’s experience during Ziprisz’s absence, and it all sounds strikingly familiar: “Everybody settled down as if for a siege; some weeks passed. The strict guarding of borders and traffic proved successful, but there were a few cholera cases near the river. My grandfather’s instructions were followed: the sick were isolated and all contacts traced and isolated as well.”

Even if the date was shortly before Robert Koch’s discovery of the cholera bacillus in 1883, there was an emerging medical consensus that the disease was transmitted via drinking water. (Unlike previous occasions, the 1881 pandemic failed to spread in Britain because of the widespread adoption of Victorian sanitation). Armed with the knowledge he had, Ziprisz managed to get the disease under control inside the camp, but almost lost his life in the process.

Then, one night, a group of soldiers rode to Ziprisz’s house with the news for Theresa that her husband had cholera and was delirious – could she come at once? Leaving her maid with the children Theresa set off for the camp. As my grandmother tells the story:

“She arrived at the river and crossed in a boat. In the camp she found my grandfather very ill but alive and the disease generally subsiding. She put the fear of God into all and nursed her exhausted husband and most of the remaining patients back to health”.

A few weeks later Theresa supervised the closing of the camp and the burning of everything within it – including her own and her husband’s clothes. As my grandmother recounts: “They were ferried across the river clad in blankets and were given some new clothes by the startled military. She personally supervised the burning of the blankets and returned home – thin, tired but victorious”.

According to my grandmother, a letter soon arrived from Emperor Franz-Joseph thanking Ziprisz and offering him a knighthood. Protesting to his wife that she should have been given the honours, Ziprisz wrote back and declined the knighthood, insisting he had only done his duty as a physician.

There were no more pandemics after that, but my grandmother’s account does contain another echo of today. She writes how Ziprisz went on to pioneer smallpox and other vaccinations, which some local villagers suspected was an attempt to poison them. My young great-grandmother Flora would be used as a role model, being vaccinated in public to win over the sceptical locals. Does this not sound familiar?

Difficult as it has been this year to cope with the impact of coronavirus, I find it a comfort to read about my great-great-grandfather’s work. His bravery as a frontline medical professional in an even more deadly time reminds us of similar bravery now. And the way science helped and protected him reminds us of the life-saving research and discoveries that will bring today’s pandemic to an end.

Levelling the Playing Field

Levelling the Playing Field

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

Barclays and Labour's growth plan

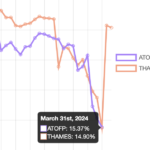

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Plummeting bonds reflect souring UK mood for outsourcing and privatisation

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital

Dimon rolls trading dice with excess capital